Cassim & Abdallah

A feature film

set in Southern India and New South Wales in the 1860s

A feature film

set in Southern India and New South Wales in the 1860s

Two young men from southern India find themselves in New South Wales around 1860, having arrived there by working on an Arab ship. They come from the area around Thalassery, a major port of trade on the Malabar coast, known for trading the famed spices of the region, especially the black pepper – known as black gold and the king of spices.

The “older” man – Mahomet Cassim, aged just 24 – is a skilled practitioner of Malabar’s traditionally ferocious martial art, kalarippayattu, an art that had so frightened the British that they tried to ban it. The younger man – Mahomet Abdallah, only 17 – is not a master of the martial art, but he is competent as an acrobat and assists his friend and mentor with total devotion.

Together, the two men aim to perform with swords and sticks, embellishing their act with feats of dance-like acrobatics. They will perform wherever they can find an audience, conquer the world, and send riches home to their impoverished families.

Part of their dream comes true. The novelty of their performance is met with amazement on roadsides and then with acclaim from crowds visiting Australia’s finest circus. But they also find disaster, one of the two Black performers dangling at the end of a rope in a botched hanging, and the other, his lungs gravely ill, sent back to India in “self-exile” after three years of hard labour cutting blocks of sandstone in Sydney’s infamous Darlinghurst Gaol.

This is a story of two young men, innocent but star-crossed, whose only crime is traveling and entertaining the public in a totally foreign land and culture. As such, it recalls the stories of millions of people who have left their homelands, willingly or unwillingly, for other shores. In particular, it is the story of these two men and the evolution of their friendship. The master teacher must face his own mortality. The servant and pupil struggles to be as strong and focussed as the master he is losing.

* * * * *

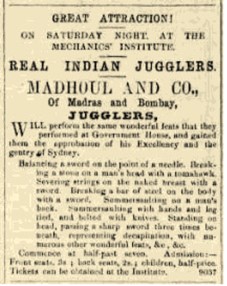

For the past three years, an international team from the USA, Australia, India, and Germany has been researching the subjects of this cross-cultural project, uncovering and reconstructing the tragic story of Cassim and Abdallah. The team has scoured archives and contemporary newspapers, reconstructed lost stories, and identified and visited remote and forgotten locations. Australian newspaper advertisements stated that Cassim and Abdallah had performed at numerous Royal Courts in India. Perhaps true, perhaps not, but we know that Cassim was a skilled practitioner of Malabar’s ancient martial art, which has its origins among warriors and is related to dance, yoga, and Ayurvedic medicine. Under the British, warriors trained in this art were considered among the most fearsome fighters against the Raj, and the Honourable East India Company tried, in vain, to ban training in this art of the warrior.

Audiences and the press praised Cassim’s extraordinary swordwork and Abdallah’s complete trust in his companion’s ability to come within a hair’s breadth of causing him great bodily harm. People found the two slender dark-skinned men exciting and attractive – but terrifying. The pair’s dazzling performances involved doing intricate somersaults while working with multiple knives and the ribbon-like swords called urumi. People couldn’t believe their eyes.

Despite their successes, Cassim and Abdallah’s story turned tragic when the young men – who spoke only limited English – were accused of murder in a case based entirely on circumstantial evidence. Following a quick trial, Cassim was hanged to death in 1863. Abdallah did not survive his journey back to the Malabar Coast in 1866.

In this feature film of 180 minutes, the story is divided into four parts, each section beginning and ending with a song composed in the style of traditional Malabar Muslim Mappila pattu.

* * * * *

Part 1: Voyage of 2 friends

After a prologue on board the British ship carrying Abdallah back to India, the film shifts to Cassim and Abdallah’s childhood in Malabar, as recounted by Abdallah to another Indian sailor. We learn of Abdallah’s family and background as the son of impoverished Muslim seamen on the coast near Tellicherry. Their language is Malayalam. Men from the Malabar Coast were known to be seafarers, travelling to distant shores to earn fame, fortune, and a name for themselves. The young men were used to the idea of aspiring to make it big in distant countries.

Like other boys, Abdallah has some training in kalarippayattu, but he shows more talent for the Ayurvedic medical traditions that are part of the region’s traditional martial art. Further north in Malabar, we see Cassim’s training and his early mastering of the martial art.

He wins a local competition and is invited to perform for the Beevi (queen) of Arakkal, a small Muslim principality in Cannanore. We learn of Cassim and Abdallah working on board a large ocean-going dhow and how young men are trained – and abused – by the vessel’s masters. Cassim takes the younger Abdallah under his wing, and they become close friends.

Part 2: Discovering Sydney and New South Wales.

After coming ashore in New South Wales, Cassim and Abdallah have to learn about life in a large port city on this remote edge of the world. While struggling to understand the language and culture, they make a modest living as buskers, performing feats of acrobatics and swordsmanship on the streets, the racecourses, and the goldfields. In Sydney, they encounter a German band, its players members of an extended family of bandsmen – Pfälzer Musikanten – from Southwestern Germany led by their Kapellmeister, Michael Gilcher. The Indians and the Germans perform for each other and become friends, music and performance overcoming the language barriers. They realise they are all wanderers in search of a brighter future. Gilcher’s band will turn up again in the course of the story.

Cassim and Abdallah take to the roads leading south from Sydney, hoping to make money by performing on the colony’s famous gold fields. They struggle to survive until they meet an Indian Muslim who calls himself Cassarotti (he has a mixed Italian and Bengali background). Cassarotti speaks English and Hindustani and understands the two men from Malabar. Assuming the stage name of “Madhoul,” Cassarotti becomes their manager. He is a godsend, organizing performances in public halls and assembly rooms, where they can charge admission. The three men begin to flourish.

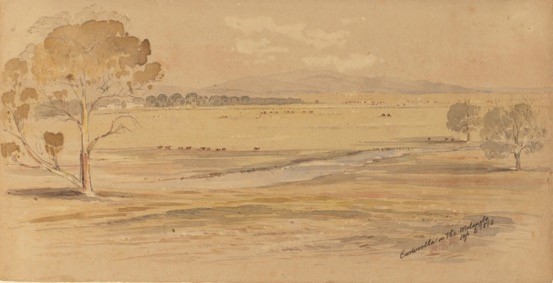

All goes well until they venture into the dangerous bush of the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales. Heading east out of the town of Queanbeyan, where they had performed in an inn, they camp in the country near the hut of a shepherd named James Robinson and his employee, William Bishop, both former convicts.

On their way to gold fields further east, the Indians hope to organise a performance at Thomas Rutledge’s Carwoola, a major sheep station. The shearing season draws many transients eager for work. When the performers wake up in their tent the next morning, their hobbled horses are missing.

All goes well until they venture into the dangerous bush of the Southern Tablelands of New South Wales. Heading east out of the town of Queanbeyan, where they had performed in an inn, they camp in the country near the hut of a shepherd named James Robinson and his employee, William Bishop, both former convicts. On their way to gold fields further east, the Indians hope to organise a performance at Thomas Rutledge’s Carwoola, a major sheep station. The shearing season draws many transients eager for work. When the performers wake up in their tent the next morning, their hobbled horses are missing. With Bishop’s help, they tramp through the bush looking for their strayed horses – unsuccessfully.

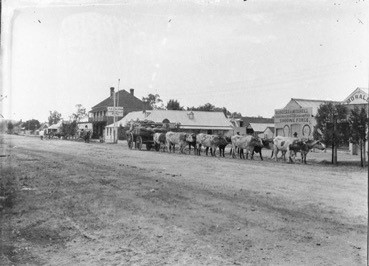

Then, one morning a few days later, Cassarotti also disappears into the bush, taking their earnings with him, money they had planned to send home to India. Cassim and Abdallah hunt unsuccessfully for the missing man for several days until they give up. Discouraged, they perform at Carwoola without Cassarotti’s assistance as master of ceremonies. Catching a ride on a bullock-drawn dray carrying wool to market, they travel towards Sydney, angry and humiliated. As they are re-loading their goods on the dray after a near spill on a bend in a muddy track, Cassim tells the drayman who is giving them a ride that if he found the man who stole their money, and he was another Indian, he would kill him – flourishing a sword over his head to show precisely what he means.

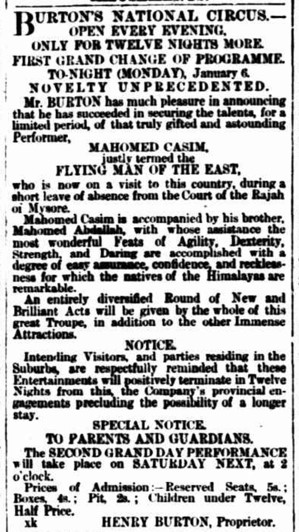

Part 3: Life with the Circus

The two men’s fortunes recover in Sydney. They meet a theatrical agent, who watches them perform and immediately contacts Henry Burton’s National Circus, an equestrian and variety show famous throughout the eastern colonies. Burton needs a new novelty act – and Cassim and Abdallah will fill the bill. The two Indians will not only provide a novelty on Burton’s circus programme but a departure from the customary menu of bareback riding, clowning, and juggling offered by a colonial circus. The two Indians quickly travel to join Burton in Adelaide. Once there, they hear the circus’s German band – it is Michael Gilcher. They are happy to find their old friends, and now they can work together. For Cassim and Abdallah, this is a new level of performance, and they can command top pay. Nonetheless, Cassim doesn’t really like the idea of entertaining people in a circus. His is a martial art, the stuff of warriors and not the stuff of entertainment, especially in a travelling colonial circus conducted by an Englishman. Abdallah reminds him that the pay is good, and they will be able to thrive – and travel back to Malabar with money in their pockets. Burton’s Circus is very popular in the colony, relieving the boredom of life on the frontier. It is hard work, though, because all the performers, including the bandsmen, have to suffer through the circus’s frequent one- or two-night stands, putting up tents and taking them down, caring of temperamental horses, and travelling along muddy tracks and crossing bridgeless rivers. As the circus travels from town to town, Cassim and Abdallah recognise many places and surrounding countryside they had visited the previous year when travelling with Cassarotti, nowhere more so than when Burton’s Circus reaches the town of Queanbeyan in October 1862. By then, Cassarotti is only a distant, unpleasant memory.

After Burton’s Circus reaches the port city of Newcastle in late December 1862, Cassim and Abdallah, along with several other performers, leave Henry Burton’s National Circus. Perhaps they want to be independent, or perhaps the circus-owner found the Indians too expensive – and no longer the novelty they had been a year earlier. They make their way southward from place to place, stopping in Liverpool, just west of Sydney.

After Burton’s Circus reaches the port city of Newcastle in late December 1862, Cassim and Abdallah, along with several other performers, leave Henry Burton’s National Circus. Perhaps they want to be independent, or perhaps the circus-owner found the Indians too expensive – and no longer the novelty they had been a year earlier. They make their way southward from place to place, stopping in Liverpool, just west of Sydney.

In January 1863, about 15 months after Cassarotti had disappeared, a man’s skeletal remains are discovered in a remote location called “Sawpit Gully,” not too far from Robinson’s hut, where the Indians had camped in November 1861. The dead man had been murdered, attacked from behind by one or two people with bladed weapons. Near the remains lie some clues as to the identity of the victim. Some of these clues appear to have been deliberately planted to implicate the two young men from Malabar as the assailants. The two performers – by this time household names throughout New South Wales – are soon arrested at Liverpool. Cassim and Abdallah – whose English remains limited – are hauled off in irons to Queanbeyan to face charges of wilful murder.

Part 4: In the gears of colonial justice

In the small town of Queanbeyan, where nothing much of importance ever seems to happen, the discovery of the remains and the subsequent arrest of the two Indians are a sensation. The editor of the local newspaper proclaims that “The elder of the men is of a very fierce and forbidding countenance, just such a man as one would judge to be capable of any atrocity; but the younger man is of a very pleasing and innocent countenance, presenting not the slightest characteristic of a murderer.” Relying on the testimonies of people who remembered the two Indian performers and their manager when they visited the area and lost their horses 15 months earlier, the Queanbeyan police quickly assemble a case. James Robinson and William Bishop, near whose hut they had camped, deny ever having helped them look for their horses. A local man who grew up in West Bengal translates between English and Bengali – which Cassim and Abdallah speak about as well as they speak English, which is to say, minimally. Not really understanding the situation and bewildered by what is happening, they make no statement other than to protest that the witnesses are lying – especially William Bishop.

The Queanbeyan court does not handle trials for murder, so Cassim and Abdallah are walked in irons to Goulburn, where the Circuit Court meets in March 1863, presided over by a Justice of the colony’s Supreme Court, Edward Wise. The judge, himself an Englishman, travels to Goulburn from Sydney for the set of trials with his retinue of officials. In Goulburn, the court provides a barrister and a translator – of sorts – who speaks Hindustani (a variation of Hindi/Urdu), which Cassim and Abdallah more or less understand. The defence attorney, who scarcely knows the case, attempts nonetheless to suggest to the court that there are many alternatives to believing that the two men on trial committed the crime. Despite the lack of substantial evidence and no unequivocal proof that the remains found in the bush are actually those of the missing man, the two men are convicted after two hours of deliberations.

Upon hearing the verdict, Cassim, the older and stronger man, faints, and Abdallah realises that he must now take the lead. He quickly stands up and tells the court all he remembers about their wanderings during the previous year. But he cannot say what happened to the missing man, because they simply do not know. Justice Wise puts on the black cap and sentences them both to death.

The case is automatically appealed to the Governor and Legislative Council. The government is relieved that a jury has found the two men guilty; there had been many cases in country courts like Goulburn’s where violent men were found innocent by local juries despite strong evidence of their guilt. With Judge Wise’s acquiescence, Abdallah’s sentence is reduced to life at hard labour, the first three years in irons. But Cassim’s death sentence is upheld. Abdallah is to be sent to the notorious penal establishment on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour.

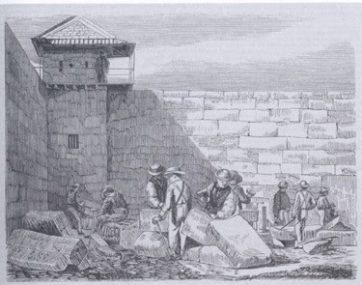

Proclaiming his Muslim faith, Cassim is not afraid to face death. Abdallah deeply admires the bravery of his friend and mentor and helps Cassim prepare for death with ritual and prayer. Cassim goes to his death on the gallows with dignity and courage. Yet the hanging is botched, leaving him twisting in the air to suffer for many minutes to the horror of the official witnesses. The devastate Abdallah is taken to Sydney’s Darlinghurst Gaol; there the prison’s surgeon does not consider Abdallah strong or healthy enough to withstand the harsh rigours of Cockatoo Island. Instead, he is put to work cutting sandstone at Darlinghurst.

Part 5 : Final verdict

In the goal, Abdallah is a model prisoner, cutting more sandstone than any other convict. It is his only hope for release. He also attends school and improves his English. Three years pass by in the prison setting, where noise, stench, violence, and attempted break-outs are the only events that break a mind-numbing routine. One day, however, Michael Gilcher and two young boys from the German band, temporarily in Sydney with Burton’s Circus, visit Abdallah at Darlinghurst, raising his spirits.

* * * * *

In the months after the trial and execution, the high-profile case of Cassim and Abdallah attracts a high degree of public interest. During and after the trial, a major debate arises in the press. After Cassim’s execution, the New South Wales Parliament launches an official inquiry. Many journalists and members of parliament are angry about the sentence of death given in a case like this where the evidence is almost entirely circumstantial. Writers and politicians alike fear that the two Indians were convicted not because of the evidence (scanty and tampered with) but rather because they spoke poor English, were foreigners, black, and Muslim.

As the months and years pass, constant inhalation of dust from the stonecutting critically injures his health. His lungs are damaged. The gaol’s surgeon fears that he may develop tuberculosis, and endanger the gaol’s entire population. After the death of Justice Wise and with the support of politicians who had followed the case, Abdallah is granted clemency on the condition of “self-exile” back to India. He is placed on a P&O mail ship, the “Ellora,” where he can work his passage to Ceylon and then on to Malabar. But he doesn’t survive the journey and never makes it home. According to descendants of his family in Malabar, Abdallah’s sister cried every day for the rest of her life.

Part 6 : History inscribed on the hearts of emigrants.

In an epilogue to the story, we mark the lives of the two men: First, by a proper religious graveside service in the Goulburn cemetery in memory of Cassim. And, finally, on the shore in Thalassery (Malabar), where we celebrate bringing Cassim and Abdallah’s story home. We see kalarippayattu and a German band performing while small dhows pull out to sea and others return.